Looking at ways of grounding the traveller’s mindset in our home towns and cities, I chatted with Shawn Micallef, urban columnist for the Toronto Star, editor and co-owner of Spacing magazine and teacher of urban civic citizenship at the University of Toronto, about the flâneur philosophy, psychogeography and the things you can only discover through walking.

Many people have talked about how travel makes it easier for us to see the world anew. How, stripped from routine and familiarity, we can interact with our surroundings in a completely different manner. What I’m exploring is just how much of this is possible for us to have in our everyday lives, in our hometowns, our work, our ‘familiar surroundings’.

I saw you described as a flâneur, what does that mean to you and how does this influence your day-to-day life?

Flâneur is a word that has been applied to me, (one that I find perhaps a little bit embarrassing), a guiding principle. It’s about being a good observer, about peripatetic observation, blending in, hopefully becoming invisible. This is where the idea of a flâneur becomes an unequal one, not everyone can blend in. As a white male that is so much easier. Lauren Elkin has released a book called Flâneuse this summer, looking at the flâneur from a woman’s perspective. Historically the flâneur’s gaze has been male so I’m really happy that this has been stretched out and looked at as to why it is unequal. I hope that everyone can take what they want out of that and wander, look and just keep looking.

Wandering seems to be a big part of this. Going around with a lack of purpose.

Other than wandering, right. When we walk around cities we tend to be in a hurry or looking at our devices, and we tend to look down. Not look at the places which we go through. Whereas when we are tourists we have paid all this money to get there and to not look around would seem like a waste of money. Sometimes I’m with people on a road trip and if someone is not looking out they remind each other – “look out the window!” When we are travelling it seems more instinctive to look around and pay attention to details that we would overlook at home.

Some of the work I do here in Toronto, writing especially, is to get people to be a tourist in their own city. Toronto is a big city and people tend to stay in their own neighbourhood. I bump into people who have lived in a neighbourhood their whole life and have never gone to some of the other neighbourhoods, they could be on another continent. If you live with people in the same city, society and you don’t physically go through the space, then you don’t really have an understanding of where you live or how you can relate to other people that you’re supposed to relate to.

I really feel that the mode of transport that you use to travel through a space makes a difference. Walking or taking the bus is not the same as driving.

Public transit is great because you tend to overhear people. In a place where public transit really is the city, London,Paris, etc it becomes a kind of public living room. People travel with it every day so they get comfortable, they talk to each other, put on their make up, sometimes they cut their nails which is gross. The great realisation, epiphany around walking came in 2004 when I was staying at a friend in Chelsea. I took the tube to Camden Market, and took this six-hour zig-zagging walk from Camden. It was a sunny May day and I walked through Soho, through Hyde Park where everyone was laying on the ground; it stitched together the city that was previously made out of these tiny little islands. I previously did not understand how they related to each other cause I had always taken the tube. Places that I thought were far apart were suddenly a block away from each other. It was as if tectonic plates were kind of shifting in my brain.

This kind of shift in perspective and discovering a city in a completely different way is also tied to psychogeography which I was very intrigued by when I looked into it yesterday. What is it for you and what is your relationship with it?

It’s another guiding philosophy for me, much like the flâneur. I moved to Toronto after grad school 16 years ago and I started walking around the city. As I walked, I discovered these historical movements related to walking, and psychogeography was one of them. It was started in France with the Situationists who were kind of radical Marxists upset about De Gaulle and the capitalists. They did this wild thing that they called Psychogeography, they tried to break people out of those routines or ruts that they get in the city so they could see the city.

They would do things like explore Paris using a map of London. One of the things that they did was the Dérive or the drift. They would drift through Paris taking the most appealing direction, perhaps the most unappealing direction. That’s what I was doing and then I found some friends here in Toronto who were very much into walking and we just started weekly psychogeographic walking thing. We explored so much of the city in the last decade and plus because we set out to walk for the sake of walking.

What I like about psychogeography is that it is a pseudoscience, a made up thing. It’s a little pompous and over the top so you can have a sense of humour with it. It’s a really nice umbrella where you can pull in, as a writer, all kinds of stuff. From my own experience walking through a city to the archive, the history that was there, to politics, design. It’s not like you are seeing it from one particular lens, it’s essentially about getting excited about places and thinking about where are moving through and how that geography and you, your psyche, your self work together.

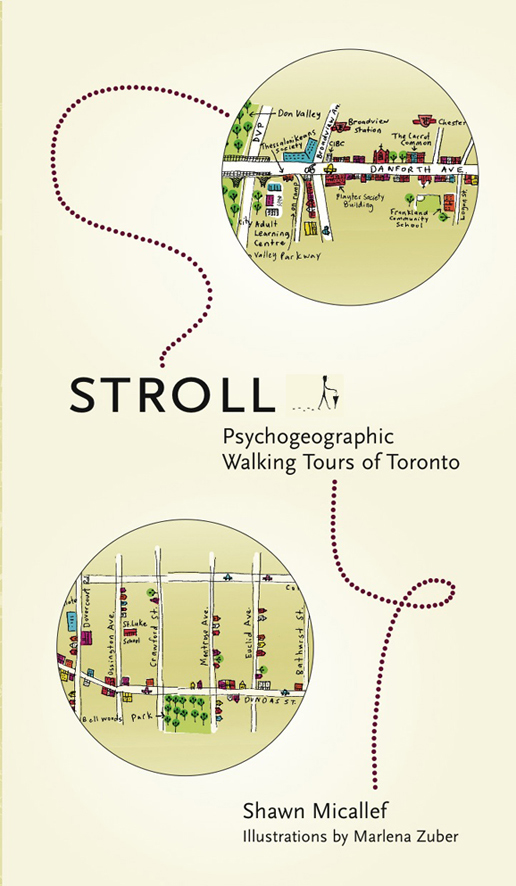

In your book Stroll, you created psychogeographic tours of Toronto.

I would go for walks in the neighbourhood I was writing about. I had a column called Psychogeography at the time, in one of the local newspapers, where I would write 1000-word essays about walking through particular neighbourhoods. Then the idea for the book came around. I had so many more notes and details. Toronto has really great public archives that I would dig through to find details about the place, also people I would talk to. Each essay expanded around five times. I give a series of starting points rather than set routes. Interesting things I found about Toronto while walking through it with an invitation for you to also walk through it and add to this, discover your own things.

In the beginning of Stroll I quote Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust: A history of walking. She has this great lines which goes:

“I suspect that the mind, like the feet, works at about three miles an hour. If this is so, then modern life is moving faster than the speed of thought, or thoughtfulness.”

Walking is the best speed at which to see things, smell things, hear things, anything faster, even biking, is faster than what you are paying attention to. This is one of the seminal works I found. I discovered flâneur, I discovered psychogeography, and then I read this book.

How important is solitude in all this?

Walking can be very lonely. Wonderfully so. And meditative. My reaction to when people ask me whether I meditate is “no”. But I do when I walk. Walking is the best thinking time. You are physically moving and that makes your thoughts move. The things you see trigger additional thoughts.

Sometimes that profound loneliness can be heavy. At the moment I am reading The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone. I was reading this in London and had a real urge to be alone. When you are walking surrounded by people you can be deep inside your own interior world. You can be present in a place physically but human contact, even though there are all these people around you, is missing. So you profoundly look at the place differently when you are not distracted by the person you are walking with. When you have no one to talk to it’s kind of like (I’m making this up here) being the radical flâneur, of being so super alone in the crowd.